Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act (FRBM Act), 2003

FRBM, Fiscal prudency & N.k. singh committee

FRBM Act 2003 Timeline

FRBM Act 2003:

The Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act (FRBM Act), 2003, establishes financial discipline to reduce fiscal deficit.

The main purpose was

- To eliminate revenue deficit of the country (building revenue surplus thereafter) and bring down the fiscal deficit to a manageable 3% of the GDP by March 2008.

- Due to the 2007 international financial crisis, the deadlines for the implementation of the targets in the act was initially postponed and subsequently suspended in 2009.

- Covid epidemic led to more delay

- N. K. Singh committee has put in place new set of recommendations which will focus towards achieving targets.

When was the FRBM Act enacted? Who introduced it in India?

The FRBM Bill was introduced by the then finance minister, Yashwant Sinha, in 2000. The Bill, approved by the Union Cabinet in 2003, became effective from July 5, 2004.

What are the objectives of the FRBM Act?

The FRBM Act aims to introduce transparency in India's fiscal management systems. The Act’s long-term objective is for India to achieve fiscal stability and to give the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) flexibility to deal with inflation in India. The FRBM Act was enacted to introduce more equitable distribution of India's debt over the years.

Key features of the FRBM Act

The FRBM Act made it mandatory for the government to place the following along with the Union Budget documents in Parliament annually:

- Medium Term Fiscal Policy Statement

- Macroeconomic Framework Statement

- Fiscal Policy Strategy Statement

The FRBM Act proposed that revenue deficit, fiscal deficit, tax revenue and the total outstanding liabilities be projected as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in the medium-term fiscal policy statement.

FRBM Act exemptions

On grounds of national security, calamity, etc, the set targets of fiscal deficits and revenue could be exceeded.

How effective has the FRBM Act been?

Several years have passed since the FRBM Act was enacted, but the Government of India has not been able to achieve targets set under it. The Act has been amended several times.

In 2013, the government introduced a change and introduced the concept of effective revenue deficit. This implies that effective revenue deficit would be equal to revenue deficit minus grants to states for the creation of capital assets. In 2016, a committee under N K Singh was set up to suggest changes to the Act. According to the government, the targets set under FRBM Act previously were too rigid.

N K Singh Committee's recommendations were as follows:

Targets: The committee suggested using debt as the primary target for fiscal policy and that the target must be achieved by 2023.

Fiscal Council: The committee proposed to create an autonomous Fiscal Council with a chairperson and two members appointed by the Centre (not employees of the government at the time of appointment)

Deviations: The committee suggested that the grounds for the government to deviate from the FRBM Act targets should be clearly specified

Borrowings: According to the suggestions of the committee, the government must not borrow from the RBI, except when...

- the Centre has to meet a temporary shortfall in receipts.

- RBI subscribes to government securities to finance any deviations

- RBI purchases government securities from the secondary market

FRBM Journey so far

A reduced fiscal deficit will help India make more investable resources available for the private sector.

In brief

- Introduced in 2003, the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act (FRBMA) aims to keep fiscal deficit under check.

- it includes escape clauses.

- in 2009, due to subprime crisis targets were relaxed.

- India’s fiscal deficit to GDP ratio peaked during pandemic.

- The government is persistently working towards reducing fiscal deficit, as seen in Budget 2023 as well.

Fiscal consolidation so far: success and failures

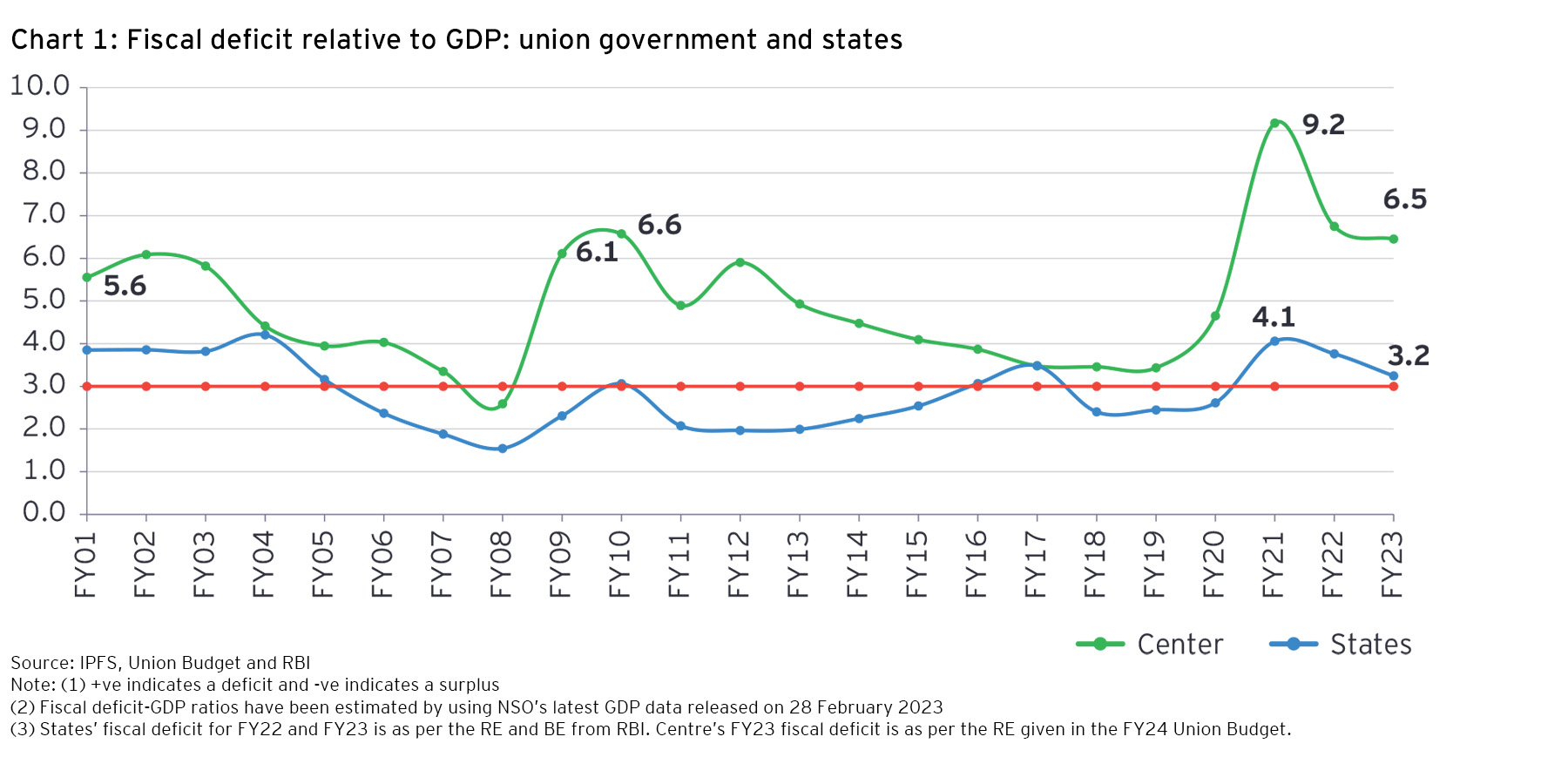

The Government of India in 2003 enacted the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act (FRBMA), which focused on reducing the fiscal deficit of the country. However, it was only in FY08 when the fiscal deficit was brought below 3%. States, who enacted their individual Fiscal Responsibility Legislations (FRLs) from 2002 to 2010 considered together, were more successful in keeping their fiscal deficit below 3% in many years.

Bringing union government’s revenue account in balance or surplus was also the part of the 2003 FRBMA and was hence, endorsed by the Twelfth Finance Commission. It became a feature of states’ FRLs. However, in the 2018 amendment to the union government’s FRBMA, revenue account balance as an objective was given up. The amended Act specified the debt-GDP targets for the union government, states and their combined accounts at 40%, 20% and 60% respectively while the fiscal deficit to GDP targets were kept at 3% each for the union government and aggregate of states.

COVID-19-induced slippages

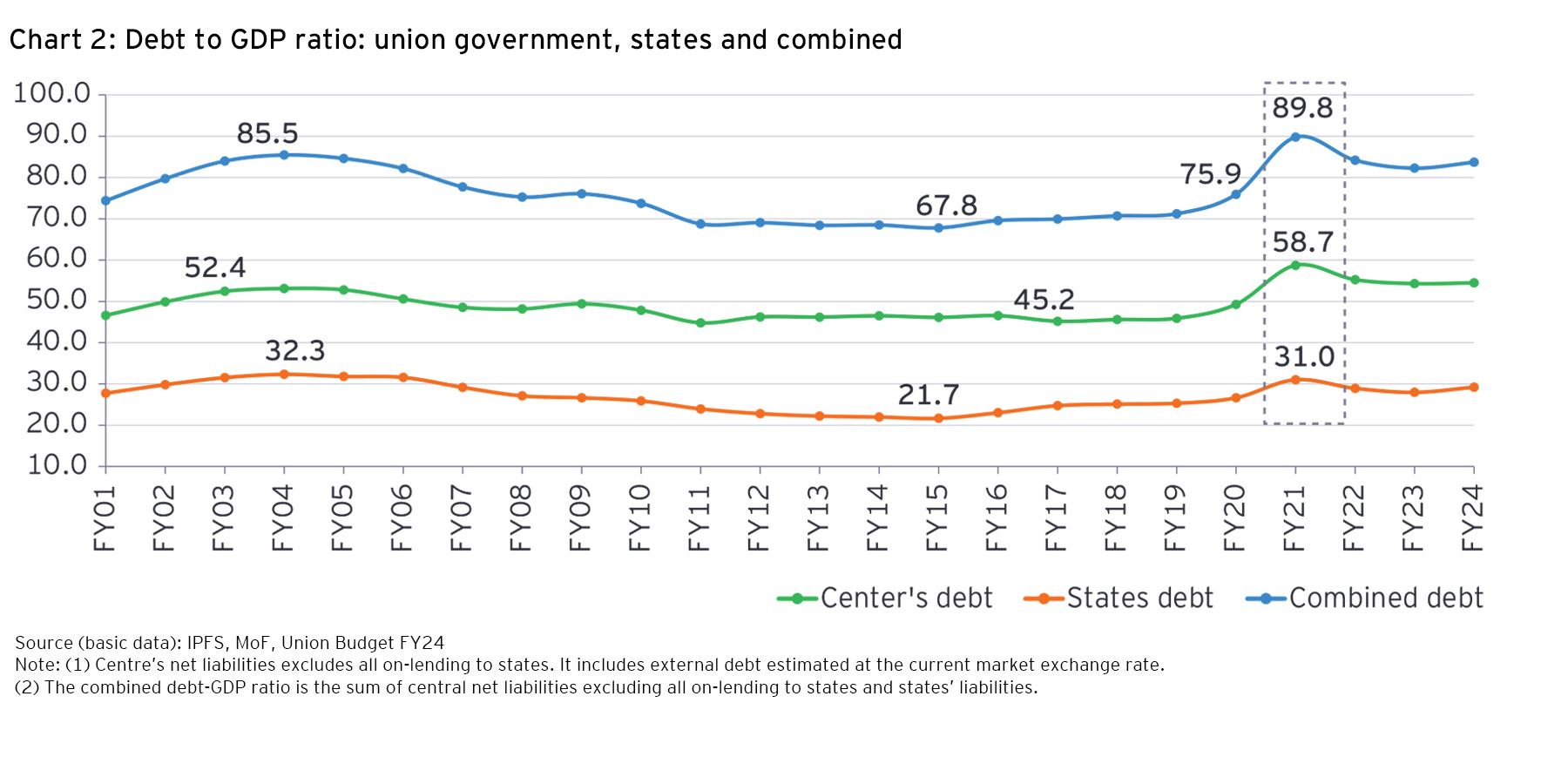

Chart 2 shows the profiles of the debt-GDP ratio of the central and state governments and on their combined account. The combined debt-GDP ratio had peaked in FY04 at 85.5%. It fell to 67.8% in FY15 after which it increased progressively to 75.9% by FY20.

With the onset of COVID-19 in FY21, India experienced a negative growth of (-)5.7% as per NSO’s second advance estimates. Even the nominal growth in this year was negative at (-)1.2%. This resulted in a major deterioration in the debt-GDP ratios across the board. The consolidated debt-GDP ratio increased sharply to close to 90% with union government’s debt-GDP ratio (excluding any on-lending to states with external debt estimated at the current market exchange rate) at 58.7% and that of states at 31%. The combined debt-GDP ratio exceeded the benchmark by nearly 30% points. Union government’s fiscal deficit to GDP ratio in the COVID-19 year peaked at 9.2%, well in excess of the operational target of 3%.

Union government’s FY24 Budget: charting a credible glide path

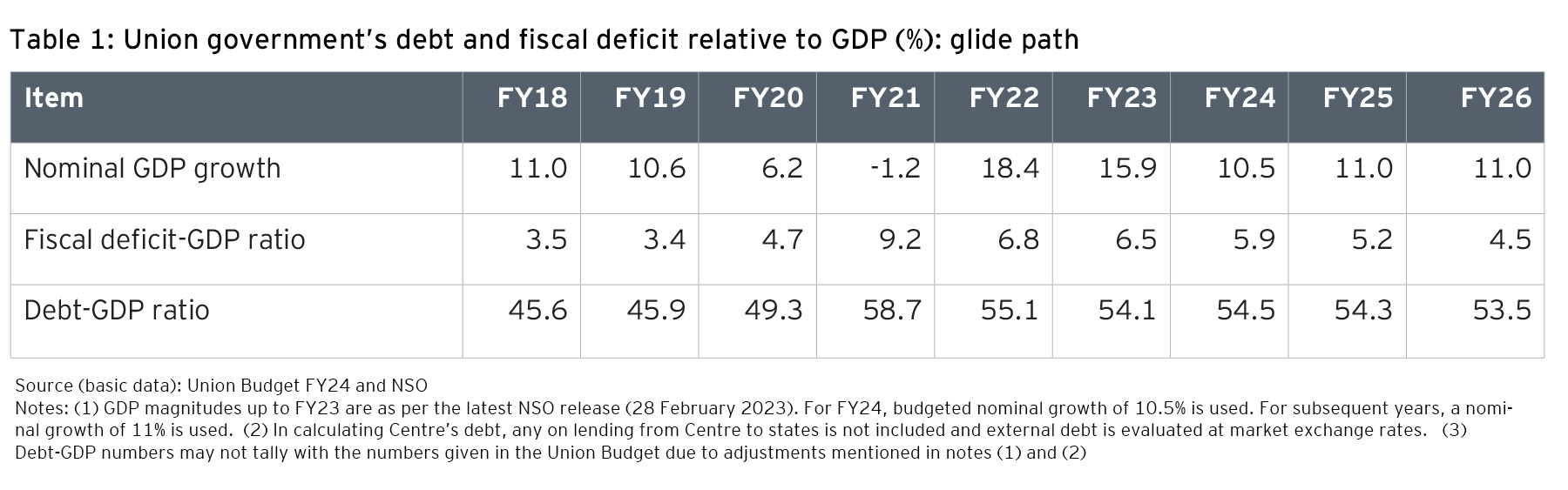

The union budgets post FY21, with positive growth rates and some effort at fiscal consolidation, resulted in a fall in the union government’s fiscal deficit to GDP ratio to 6.8% and 6.5% in FY22 and FY23, respectively. This effort was strengthened in the FY24 budget, where in spite of global economic headwinds, central government persisted with fiscal consolidation. Compared to a reduction of 0.3% points in FY23, the budgeted reduction in the fiscal deficit-GDP ratio in FY24 is 0.5% points, which according to present indications is further to be accelerated to an annual reduction of 0.7% points in the next two years, enabling a fiscal deficit level of 4.5% of GDP by FY26 (Table 1). In FY24 budget, the union government is focused on capital expenditure growth (37.4%) while limiting revenue expenditure growth to 1.2% with a view to taking advantage of the high capital expenditure multiplier. According to RBI (2019), union government’s capital expenditure peak multiplier was estimated at 3.25 while that of revenue expenditure is 0.45.

Government borrowing is a pre-emptive claim on the economy’s available investible resources. In India, it is only the household sector which has an investible surplus in the form of financial savings which presently amount to 8% of GDP. Supplementing this by a net capital inflow from abroad of nearly 2.5% of GDP, total investible resources add to 10.5% of GDP. In FY24, the combined fiscal deficit of central and state governments may amount to 9.4% of GDP, leaving limited scope for borrowing by the private sector and the PSUs. As combined fiscal deficit is brought down, progressively more investible resources would become available for the private sector. In the years after FY26, union government’s fiscal deficit may be allowed to fall by higher margins of say 0.75% points of GDP per year with a view to reaching the FRBM target in the next two years.

By FY28, a fiscal deficit-GDP ratio of 3% would be reached, but according to our estimates, assuming a nominal growth of 11%, the debt-GDP ratio would be close to 50%, 10% points above the FRBM target. Continuing with an 11% nominal growth and retaining a fiscal deficit-GDP level of 3%, the debt-GDP ratio is expected to reach 40% by FY35. As government debt as a proportion of GDP falls, the effective interest rate on government debt would also fall, reducing the interest payment to revenue receipts ratio, thereby facilitating the accelerated pace of reduction in fiscal deficit for reaching the desired target. If the implicit price deflator-based inflation is kept at 4%, a real GDP growth of 6.7% would be required over this period. Sustaining a growth rate at this level would require a suitable growth in private investment. It is only achieving the FRBM norms and adherence to these over a long period that would leave enough investible resources for the private sector to contribute to growth.